Review – L’amour fou

– by Regan Payne

L’amour fou opens with two public addresses juxtaposed against one another.

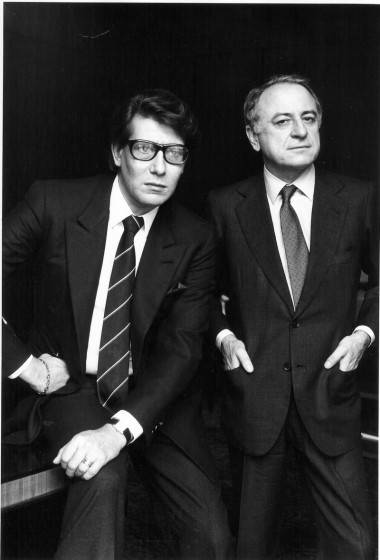

In the first, a withered, somewhat shambolic Yves Saint-Laurent, employing quotes from Rimbaud and Proust, in a circular address to the assembled media, announces his retirement from the world of haute couture fashion in 2002. The second sees Saint-Laurent’s longtime companion and business partner, Pierre Bergé’s eulogy at the great designer’s funeral from brain cancer in 2008.

It’s a fitting juxtaposition to begin with. As the film progresses, what is meant to be a feature-length cross-dissolve between two lives and their collective passion for art blurs into a thinly veiled biography, or greatest hits package, of Yves Saint-Laurent’s massive talents, and the man who feels a certain degree of credit for the Saint-Laurent brand has, perhaps, unfairly eluded him.

Ostensibly, in his documentary-directing debut, photographer/video artist/painter Pierre Thoretton chronicles the sale of the legendary art collection amassed by Saint-Laurent and Bergé in their 50-odd years together. In fact, very little of L’amour fou, save for the final 15 minutes or so, is dedicated to the art collection and its sale.

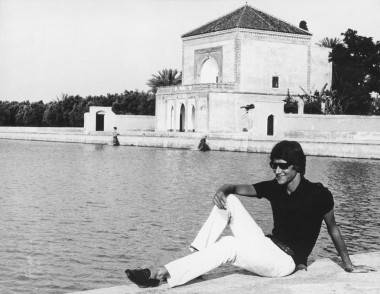

Instead, with Bergé as our guide, we are given long, beautiful tracking shots from their various homes in Morocco and Normandy interspliced with quick jump-cuts to various fashion shows, interviews, and personal home movies of their lives together.

As a film-maker myself, I always cringe when a director employs both the long dolly and quick cut simultaneously – it’s a thorny indication of lack of trust in his audience. Thoretton’s gift for shot making is not up for debate: he goes to great pains to present a warm, painterly feel to each set-up.

However, the film is told almost entirely from Bergé’s account of things and, when it is not, a small group of confidante’s is rolled in to ensure we understand Bergé’s importance to the proceedings. (In one bizarre sequence, Bergé recounts his budding friendship to former President Francois Mitterand, complete with photos, if for not other reason that I could gather, than to establish “street cred”.)

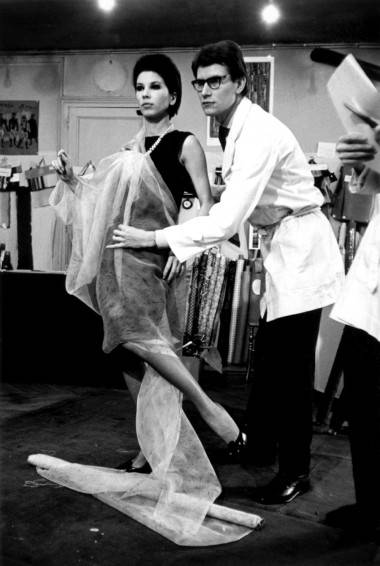

All of this would be fine, were it not for the fact that Bergé does not possess a personality that is, as Charlie Sheen would surely state, winning. What follows is a feature-length narration from Bergé as Saint-Laurent’s astonishing career (he was named successor to Christian Dior, and thus, the Dior brand and empire, at the meager age of 21) is highlighted through the societal issues, rebellions and trends of the times: all of which seemed to have heavily influenced the designer’s work.

When the massive Christie’s auction finally does place, Bergé is shown in a back room, viewing the proceedings through a monitor and pleased as punch when the bidding escalates between anonymous art collectors thanks to employees vigorously waving paddles. Bergé even admits that Saint-Laurent would not approve of his decision to sell off the collection he worked a lifetime to create.

In the end, that is the portrait we are left with – that of an artist, a truly gifted artist, wallowing, withdrawn, and broken: not “winning” at all, necessarily. Saint-Laurent spent a great deal of his final years in isolation and in pain. Bergé claims to have “tried everything” to help him, though these efforts, curiously, are not elaborated upon.

There is a brief moment, late in the film, where Bergé and Saint-Laurent exchange an embrace and kiss. Thoretton removes the audio track and the moment is viewed in quaint silence. The five-second passage, with no sound, shows everything Bergé has spent the other 80 minutes or so trying to persuade us of: that he adored Saint-Laurent. And in that brief moment, Thoretton shows his ability to allow his audience inside, if only for a moment, to connect to his subject, in a way his subject can’t express adequately himself.

L’amour fou opens today (June 17) in Vancouver at Fifth Avenue Cinemas.