Interview with Tom Roston

– by Jonathan Parkin

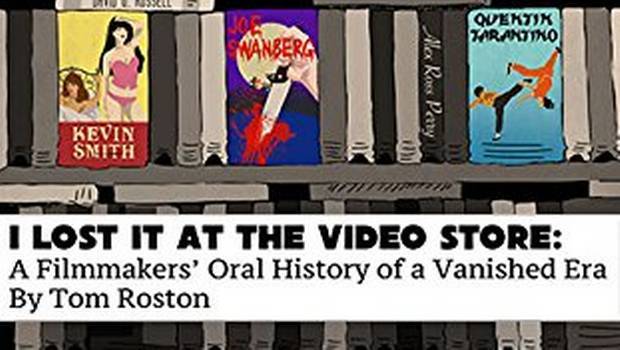

Nostalgia lies at the heart of Tom Roston’s new book I Lost It at the Video Store. And that nostalgia has resounded with enough people to make it one of the best indie books of 2015, according to Kirkus Reviews.

In a way, there’s never been a better time for a book like this than right now. For many, the years of the video store were a golden age. Growing up during that brief, star-studded period carried all sorts of entertaining prospects for those fortunate enough to be a kid at the time. Yet though it seemed we were deluged with diversion, for many of us the most convenient place to visit was the local video store. It might have been family-owned and operated or part of a major chain like Blockbuster or Rogers, but chances are it had a particular sentimental value to it – and not just because of its treasure trove of videos that far outshone our own modest selection of VHS cassettes.

Roston brings us back to this magical period in our lives. A long-time journalist himself with multiple connections in the film industry, he uses his own prose as well as extensive interviews with people in the industry (notably Allison Anders, Darren Aronofsky, and Quentin Tarantino) to elicit a recollection of the past that strikes our own hearts and that special place the video store had in them.

It isn’t just nostalgic value that Roston brings back to us. As his interviewees relate, the video store phenomenon played a great role both in viewers’ lives and the filmmaking industry itself. The story of the direct-to-video boom times, the insurgent rush of independent films, the emergence of low-budget directors who would eventually become known as makers of cult classics – are facets that Roston explores in loving detail.

Video – I Lost It at the Video Store:

Jonathan Parkin: What’s your background? How did you get into what you’re into now?

Tom Roston: I’ve been a journalist for 20 years, and I started out at Premiere Magazine. I worked there for 10 years, and that’s where I got my focus on movies. After that, when all the old media magazines shut down I became a freelance writer, and I came up with this idea.

JP: Nostalgia’s been a big thing to this generation. What inspired you to write a book like this? What did the video store mean to you?

TR: Nostalgia’s a big part of it, definitely. About 2013, Blockbuster closed its last store – they’d filed for bankruptcy a few years before that. There were a lot of journalists talking about their old memories, and like you said, nostalgia. They were talking about “Oh, it’s the end of an era,” about their favourite video stores, and I thought, “Well, what about the filmmakers? I’d love to hear from the filmmakers, what they have to say.” And, as you know, Quentin Tarantino, Kevin Smith –Â there’s a whole generation of filmmakers who were raised in the video store. I thought I and a lot of other people would be interested to hear about it, that they’d be interested in sharing their opinions. I think it’s because they have a lot of affection, they identify with the video store era, and that’s why they took time from their own projects.

JP: I’d like to hear about what kind of movies you grew up with. Which one was your favourite? What was the experience like for you specifically?

TR: As much as I was into it aesthetically, as much as I could be as a teenager, that wasn’t the primary interest for me. The fact that I could enter the video store, and everywhere I’d turn there’d be a new culture, storyline, that I could tap into. Whether it was like a macho Schwarzenegger movie – I could see some guy kick ass – but also as I got older, I learned how to be a different kind of person. Basically with video stores, on every shelf you’d find new ways to live – to me it was really a kind of coming of age kind of thing. Only later did I come to appreciate films as an art form.

JP: Now in terms of appreciating film as an art form, to what extent have you been involved in the film industry? How did you get to know all these directors?

TR: I’ve never really made movies – I’ve dabbled a little bit, worked on other peoples scripts, but nothing much. I’ve reported on the film industry for 20 year now. Just, some friends might have had a script and asked me to write a scene, but nothing major. They got produced, but nothing big. It sounds more exciting than it is, really. Getting to know people, the making of films, getting to see how these great people did their work. It was different for every filmmaker – some of them I already had contacts with, like Nelson and Aronofsky – it was kind of like this ad hoc way of approaching different people.

JP: What do you think the value of the video store is today, if any? Just nostalgia? Is there a future for them?

TR: For me it’s just nostalgia but for a lot of people it’s a valid, legitimate way to exist. There are a number of successful video stores in Los Angeles, and there are many across the country. Much fewer than there used to be. I do think the video store era is over, but for lack of a better analogy people still play chess even though there’s Call of Duty. There’s an analog world that people still wanna live in, thank God, instead of just via computer or iPhone. So I think video stores are going to continue to exist – they’ll just be harder to maintain. A lot of them are nonprofit.

JP:Â Do you think that services like Netflix incentivize playing it safe, and reduce the opportunity of new filmmakers to court controversy?

TR: If you look at it in the context of the video store era – basically, the distributors in video stores knew there were, say, X number of people that wanted to see genre films, sexploitation films, and who wanted to see weird films about aliens. It was definitely encouraged. And we can credit the video store for definitely giving them a space – there were shelves that needed to be filled, so they definitely gave independent films an opening.

Now, streaming services like Netflix will support independent filmmaking, but because there’s so much material out there, if you’re an independent filmmaker trying to get your weird little movie noticed, you can put it out there yourself but who’s going to see it? It’s true Netflix doesn’t always give them the support it could, so it’s an interesting trend to follow.

JP: As streaming services gain their own studios, how do you think they that will affect the film industry?

TR: I think there’s a lot, actually. I think Netflix is putting so much money behind these talented directors, Adam Sandler aside, you know Leo DiCaprio, Spike Lee – I think they’re encouraging a lot of talented filmmakers to come over.

I spend a lot of time talking to people about this, though, and I think there is a void. I think a lot of people are frustrated going over their Netflix and their Amazon Prime queues and they want something that’s going to speak to them, leading to better curation, better availability, a better sense of community. I think we’re in a transition, and someone’s going to have to step up. Netflix is in the best position, they’ve got the market cornered, and they’ve got a lot of clout, but I don’t think they’re necessarily the evil empire. I’m hoping that they’re going to provide something that will fill that void.

Pingback: I Lost It at the Video Store: my first published work | Genie's Teeth