Interview – Roddy Doyle

– by Shawn Conner

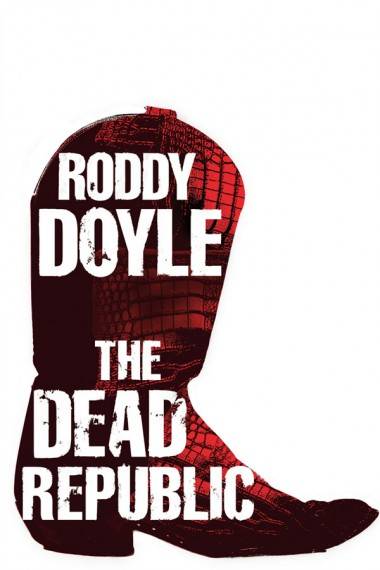

The Dead Republic, Roddy Doyle’s latest novel, is the third in the Henry Smart trilogy begun in A Star Called Henry (1999). Where the first book described the extremely impoverished conditions that led to the 1916 War of Independence, and the second – Oh, Play That Thing! (2004) – covered Smart’s American adventures, The Dead Republic gives readers both a glimpse into Old Hollywood (Smart is hired by director John Ford as a consultant for the film The Quiet Man) as well as the fractured and fractious final days of the IRA.

Doyle is also the author of The Commitments (the basis for the movie of the same name), The Snapper and The Van, all of which make up what is informally known as “the Barrytown trilogy”. He won the 1993 Booker Prize for Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha and has written two other novels, The Woman Who Walked Into Doors and Paula Spencer, a memoir about his parents called Rory and Ita, plays, the screenplay for the romantic comedy When Brendan Met Trudy, children’s books, and numerous short stories, including the 2008 collection The Deportees.

We sat down with the Irish author at Vancouver’s Shangri-La Hotel on the last stop of his North American book tour for The Dead Republic.

Shawn Conner: What was your childhood like, where the IRA was concerned?

Roddy Doyle: The Troubles, as they were called, started when I was 11 or 12. A lot of the veterans of the War of Independence [1916] were still alive. Those that hadn’t been executed. It was history, but it was living history. I don’t know if I was even aware of a place called Northern Island…

It was all black and white for awhile. Catholics were being burnt out of their homes. Refugees were coming over the border. There was one in my class in high school, this kid, suddenly there. His family home had been burnt to the ground. It was the good guys versus the bad guys. It probably reached a peak in 1972 with Bloody Sunday. I was in my first year at high school. British paratroopers opened up on a crowd demonstrating in Derry and killed 13. The claim was they [the demonstrators] were all armed and they were firing at the British army. It was just nonsense. They shot indiscriminately.

There was a level of fury I recall vividly; the following Wednesday, the British Embassy in Dublin was burnt down. And this was just up the road a few miles away. I remember watching it with my parents, then going to school the day after – and I never met anyone who thought this was a bad thing. And these were law-abiding people. It seemed like a reasonable response to what had happened [in Derry].

Then it got complicated. These so-called freedom fighters were planting bombs in pubs in Britain. People who were just havin’ a pint on a Friday night were being killed. Girls who went out with British soldiers were being tarred and feathered. Teenage boys who didn’t do what the IRA said were being kneecapped.

SC: Which is in the book. The tarring and feathering isn’t…

RD: Well I didn’t feel a burning need…

SC: It’s interesting hearing you talk about all this and realize all of this history is in The Dead Republic but in a different form. Was it difficult writing a character who is both an individual and emblematic of decades of history?

RD: The initial idea is quite easy, the difficulty lies in sitting down and accepting some words and rejecting others, and every character has that difficulty.

SC: Will you be glad to get away from Irish history in your next novel?

RD: Oh yeah. I took a break, I wrote a novel called Paula Spencer, and I’ve written other things. But yeah, the formal research – I love reading, but when you have to, it’s homework. You’re taking notes.

SC: Was it fun to write about Old Hollywood and people like John Ford, Henry Fonda and John Wayne?

RD: I was a little bit nervous about Maureen O’Hara, she’s still alive. She had her own memoir, ‘Tis Herself, I read that as well.

SC: Did any of that make it in?

RD:Â Only a sense of her feistiness. And I had a sense of the streets she grew up in, and they were the same ones Henry would have lurked around in during the War of Independence.

SC: There’s something you once said I find myself thinking about fairly often, it was writerly advice – to not wear headphones in public places like the bus because you might miss something, a phrase or verbal exchange…

RD:Â Well I’ve changed my mind about that! I do think it’s sound advice, but if it’s religiously adhered to you’re denying the pleasure of listening to music while you walk. I was given an iPod and was converted.

SC: Are you still surprised by Irish dialect and vernacular?

RD: I am, actually. My kids come home and they know I’m listening. I have a son who works in a liquor store and he texts me, not just words but things, like if three lads come in and order 200 cans of a cheap brand called Dutch Gold, he’ll tell me.

I get worried sometimes, I hear Americanisms creeping into my daughter’s language. “The elevator” – it’s a fuckin’ lift!

One response to “Roddy Doyle”